There can be no denying that the Space Shuttle was an engineering marvel. At the time of its conception, space travel was not only seen as something incredibly exclusive, but also something that was too costly. Spacecraft were not able to be reused, many of the components needing to be made again just to get the next rocket off the ground. The Space Shuttle though was about changing that, opening up space travel and showing that it could be somewhat affordable by reusing not just the shuttle itself, but the solid rocket boosters that helped propel it into space.

But as we now know, all was not well with the Space Shuttle program. Fundamental design problems were evident from the get-go with the project, and it took far too long before those design faults were fixed. In the meantime, the Challenger Space Shuttle disaster had unfolded, and Columbia would also be tragically lost barely 20 years later. The Space Shuttle achieved great things right up until its retirement in 2011. But as a concept, it was fundamentally flawed, despite the success the entire project was able to achieve.

Not As Easy To Travel Into Space

The original aim of the Space Shuttle was to, hopefully, almost open up space travel to the masses. NASA had initially hoped for some 60 flights a year of the shuttle, or around two a week. This was a hugely ambitious target, but in the late 1970s and right up until Columbia’s first launch, NASA believed that this was possible. Once the complexities of the shuttle were realized though, and the difficulty in refurbishing the solid rocket boosters was seen, NASA realized they had perhaps bitten off a bit more than they could chew with the shuttle.

Multiple shuttle launches would be delayed, including the fatal Challenger mission. Challenger was originally scheduled to launch on January 22nd, 1986, but it didn’t launch off the ground for its final flight until January 28th, and this was after it had been delayed originally after being scheduled to launch in November 1985. With so many shuttle missions having delays or minor issues, pressure had ramped up at the highest level within NASA to make sure they stuck to some sort of schedule. These pressures would ultimately lead to the fatal decision to launch Challenger on that January day.

Issues With O-Rings

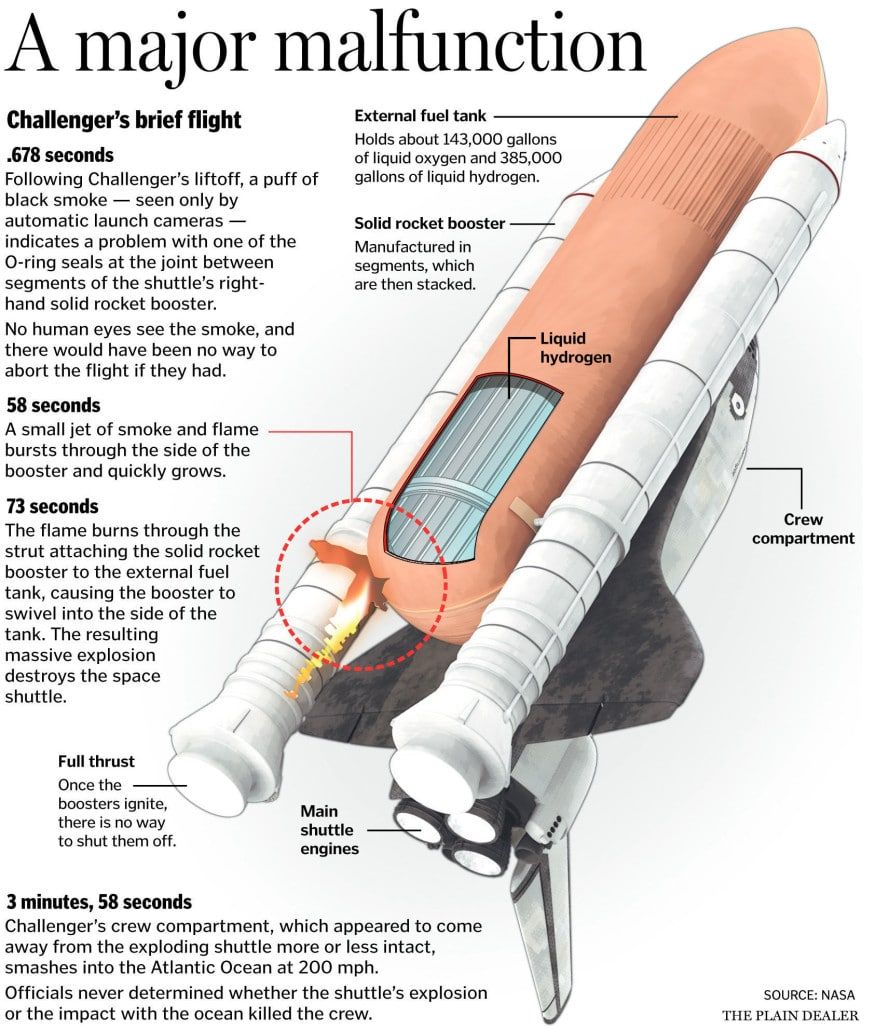

The biggest technical issue with the shuttle was the use of rubber O-ring seals on the joints of the solid rocket boosters. Where there were joins in the boosters, two O-rings were there to form a seal. There was a primary ring, and a secondary to cover off a failure of the primary ring. But on many shuttle launches, the boosters would come back with issues around the O-rings. A correlation was soon discovered between the colder the temperature outside affective the rings and stopping them from sealing, which could allow the hot, high-pressure gases produced by the solid rocket boosters to escape.

O-ring failures had occurred from the second shuttle flight onwards, with all but one of the flights in 1985 having an issue with the O-rings. The 17th shuttle flight, that used Challenger in April 1985, saw both the primary and secondary O-ring show signs of erosion. This set off alarm bells within the engineers at the solid rocket boosters builders, Morton Thiokol. Men such as Allan McDonald and Roger Boisjoly wanted the design changed and improved upon, and whilst this was approved, NASA and the managers at Thiokol allowed for the usage of these faulty boosters in the meantime. This decision would ultimately prove fatal

Challengers Final Flight

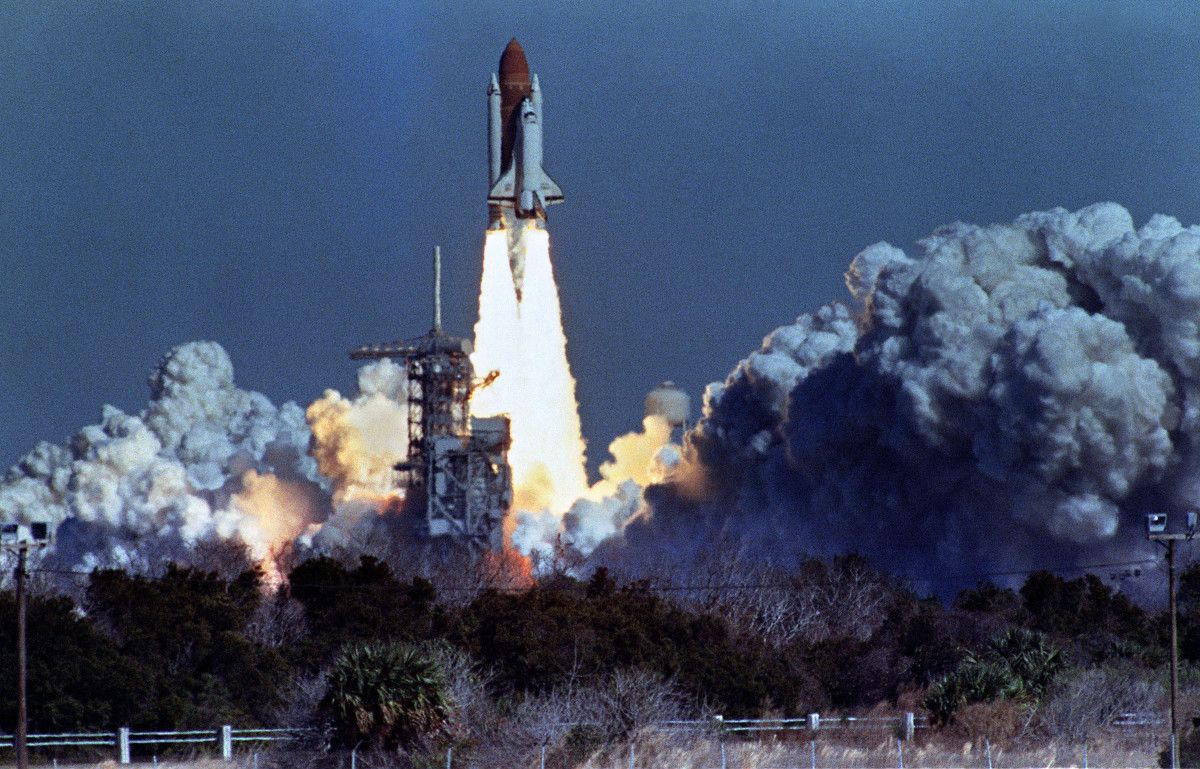

The Challenger disaster would ultimately be what put the failings of NASA, Thiokol’s management, and the shuttle design in the spotlight. Some 73 seconds into its flight on January 28th, Challenger and its external fuel tank disintegrated, killing all seven astronauts including Teacher in Space, Christa McAuliffe. The O-rings had indeed failed on the right-side rocket booster, failing at launch before sealing themselves up again as the Shuttle took off. The effects of the Jetstream played a part in causing the seal to fail again at altitude, which led to the disaster.

Could NASA have done more to save the crew? Most definitely. Thiokol had argued that the temperatures on January 28th would be too cold for the O-rings, with most issues on the rings having been spotted on colder launch dates. The engineers recommended not to launch, and it had been so cold the night prior that ice had formed on the launch tower, partly also thanks to water running over the system to stop pipes freezing. Thiokol’s management overruled its engineers and NASA proceeded with the launch, highlighting the flaws in the structure around the shuttle program.

Avoidable Tragedy’s

The brake-up of Colummbia in 2003 further highlighted issues within NASA and the program, with a well-documented issue failing to be acted upon. This time it was damage from taking off that sealed Columbia’s fate as it re-entered the earth’s atmosphere. Both it and Challenger were avoidable tragedies that greatly exposed the Shuttles issues, from a technical, practical, and managerial standpoint. There is no doubt that the shuttle itself was an engineering marvel. But even the most amazing of achievements can have their downsides.